This interview was originally broadcast on BBC Radio (14 October 2020). Asking the questions is journalist Rhiannon FitzGerald. We discuss writing, botany and international development.

International development being my day-job, I would have loved the opportunity to discuss this subject further with her, as I know it is a particular interest of hers, also.

Tell us about yourself.

I’ve always loved reading, and I read anything and everything. Perhaps because of this, I have a vivid imagination which I apply to the people and things I come across on a day to day basis. I’ll pass a person on the street and create a backstory for them. A smell might spark a memory, a phrase in a song may trigger an emotion, or a news story will have me wondering ‘what if?’

My background is in plant diversity, with a specialism in taxonomy. I draw on this knowledge in LOST & WAITING. While at university, I spent time training at Kew, which features in the book.

You have a vivid writing style. Can you tell us about your methods?

Thank you. I try to write to all the senses to help the reader inhabit the action on the page.

Where I’ve not experienced a situation, I do plenty of research. When writing the earthquake scene, for example, I read first-hand accounts, some of them from authentic Victorian plant hunters. I also found videos on YouTube of recordings people have made on their smartphones as an earthquake progresses. These were invaluable as the eyewitness doesn’t have a chance to process what they are experiencing – it is just raw emotion. The internet is a wonderful thing!

What is the book about?

LOST & WAITING opens in the present day with Evangeline arriving in South America. She has discovered the journal of Victorian plant hunter Edwin Chile Morgan who claims to have discovered the mythical world tree.

The book is a mixture of contemporary and historical fiction, and myth. My writing style has been described as vivid, filmic and high-energy.

From reviews I’ve seen, the book comes across as Indiana Jones meets Moby Dick, by way of Charles Darwin.

What inspired you to write Lost & Waiting?

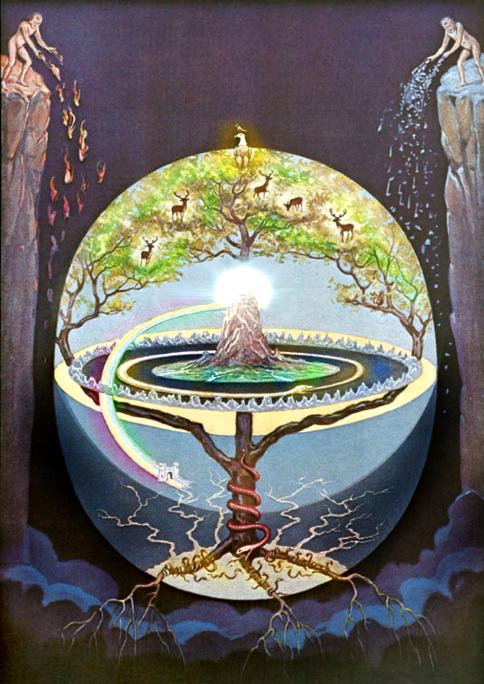

I was inspired by the myth of the world tree, a myth that crops up time and again across different cultures throughout the world. The world tree is a colossal tree that connects the sky, the earth and the underworld. This connection between all life on earth seemed like an apt metaphor for environmental and conservation issues in the world: we are all part of the one system.

Illustration from The Secret Teachings of All Ages by Manly P. Hall

Why did you write your book?

There are lots of great creative non-fiction about plants and nature. By talking about plants in a different way, fiction, I hope to draw a broader readership over to the importance of plant conservation and the threat of deforestation.

Lost & Waiting involves not one but two botanists/plant hunters. What is it about plants that interests you?

My interest in plants was originally piqued by the many different mechanisms they have evolved to reproduce, to repel predators and pests, and to survive in diverse habitats. These adaptations are necessary due to their sessile lifestyle and have given rise to the beautiful forms and fragrances we experience in nature.

I want the book to inform as much as entertain – so the reader comes away with a greater appreciation of plant life, without feeling as though they’ve been lectured. For this reason, Evangeline and Morgan had to have a certain level of expertise to guide the reader.

The setting of Lost & Waiting adds much to the texture of the story. Can you tell us why you chose to set the story in Chile?

As I said earlier, my overarching aim is to share my love of, and respect for, plants. For this reason, I set the novel in a region rich in biodiversity.

When choosing the location, my first thought was to look at the world’s biodiversity hotspots. From there, I disregarded those areas that have already had their time in the fiction spotlight, there are many books set in Brazil and China, for instance.

Chile interests me because it extends from arid desert to icy steppe, taking in around 13 terrestrial ecoregions over its 2,700-mile length. Flanked on the west by the Pacific, and the east by the Andes, the flora of Chile has been isolated for millennia and displays high levels of endemism (an endemic species is one that exists only in one geographical region). In fact, Chile has the largest percentage of endemic species in the world.

My decision to set the novel in Chile was further swayed by my love for all things Latin American. Writing about a South American country gave me an opportunity to learn more of its culture and history.

Temuco, which features in a couple of chapters, has a strong German tradition, dating from the wave of German traders immigrating during the nineteenth century. I included the city due to a Chilean arboriculturalist’s tweet I saw about a decision to hack down the trees lining Temuco’s avenues, as their branches were interfering with power lines.

How did you come up with the title?

With extreme difficulty!

All the way through writing the book, the working title had been Ya’axché (Yaxche is the Mayan world tree). There were two problems with this title. The first was geographic, it referred to the wrong culture. The main issue, though, was more basic than that and only too obvious: no one would know how to ask for it in a bookshop.

So I kept a list of possible titles, and added to it whenever anything came to mind. I must have had around 60 options, but none of them felt right. Then I turned on a documentary one evening and the presenter quoted a couple of lines from Rudyard Kipling’s The Explorer.

Something hidden. Go and find it. Go and look behind the Ranges

The Explorer, RUDYARD KIPLING

Something lost behind the Ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!

That was it. I love the imperative voice of the poem, and the mysterious ‘something’.

In addition, Rudyard Kipling wrote classic adventure stories, including The Man Who Would Be King(1888). The 1975 film of the same name, staring Sean Connery and Michael Caine, is one I watched countless times when young, along with She (1965), staring Ursula Andress (adapted from from H. Rider Haggard’s 1887 book), and the 1937 version of The Lost Horizon (based on the 1933 novel by James Hilton).

In all adventure stories from the nineteenth century, the protagonist is male. I wanted an adventure story for women.

What other books have inspired you?

Perfume (1985) by Patrick Süskind is a sensual delight, Tales of Long Ago(1965) by Enid Blyton introduced me to Greek mythology, The Picture of Dorian Gray(1890) Oscar Wilde is gloriously gothic.

What did you learn when writing Lost & Waiting?

I got to explore Chilean culture, history and flora. I also enjoyed learning about nineteenth century seafaring, such as the sailors’ superstition that whistling on ship can summon a storm. Only the ship’s cook is allowed to whistle, as it means he’s not helping himself to the food.

What can readers hope to learn from this book?

Evangeline faces many setbacks during the novel, and must keep going to reach her goal. So, perseverance figures strongly. Things don’t always go our own way, nor how we might expect, but if we want something enough, we must expect to work for it.

Aligned with this, Chile Morgan has a sense of humour and doesn’t take himself too seriously. These attributes help him through many dicey situations. I genuinely believe a positive attitude is the secret to being young at heart. Enjoy the moment!

Of course, I also hope the reader comes away with a greater appreciation for plants.

Before we go, you’ve done some really interesting work as a research programme manager for international development, so, how do plants tie in to that?

I have run several programmes bringing together researchers from the UK and overseas to tackle agricultural issues in developing countries in the regions of sub-Saharan Africa, south and south east Asia, with a view to improving livelihoods in those regions.

Agriculture is fundamental to international development as the majority of the world’s poorest people survive by farming. Research into technologies to promote growth in the agriculture sector is two to four times more effective in raising incomes among the poorest compared to other sectors.

As we develop our understanding of how diseases spread, the ways to resist both those diseases and the effects of climate change, and to ensure our food is safe and nutritious, what we have found is that the UK benefits from the research just as as much as the arable and livestock farmers, their communities and policy-makers in developing countries.